Abstract

Agile methodologies have emerged as dominant frameworks for managing adaptive processes in software development and beyond. As industries increasingly navigate turbulent markets and rapid technological advances, traditional rigid methodologies, such as Waterfall, have begun to lose relevance. Agile, in contrast, promotes iterative development, collaboration, and responsiveness, which better align with contemporary business needs. This article introduces Agile by exploring its foundations, variations, and principles, providing a comprehensive understanding of its main benefits and possible challenges. Through this exploration, readers will gain a clear insight into how Agile transforms workflows and fosters continuous innovation. The aim is to enable businesses and teams to make informed decisions about integrating Agile into their operational frameworks.

Introduction to Agile

Agile methodologies have redefined the landscape of software development and project management, creating a substantive shift from the linear, stage-gated processes defined in the 20th century to more flexible, iterative forms of production. Agile was introduced as a response to the shortfalls of traditional linear methodologies—most notably the Waterfall model. While Waterfall adheres to a sequential design process where each phase must be completed before moving to the next, Agile emphasizes adaptability, customer collaboration, and continuous delivery.

At its core, Agile provides a framework where teams incrementally build and improve their products, thereby remaining flexible in rapidly changing business environments. In doing so, Agile enables organizations to produce work that better addresses customer needs and market demands. The key tenets of Agile involve iterative cycles called “sprints,” where prioritized features or customer needs are addressed, tested, and reviewed with stakeholders. This process contrasts dramatically with the rigid upfront planning of Waterfall, where gathering comprehensive requirements before any work begins is paramount.

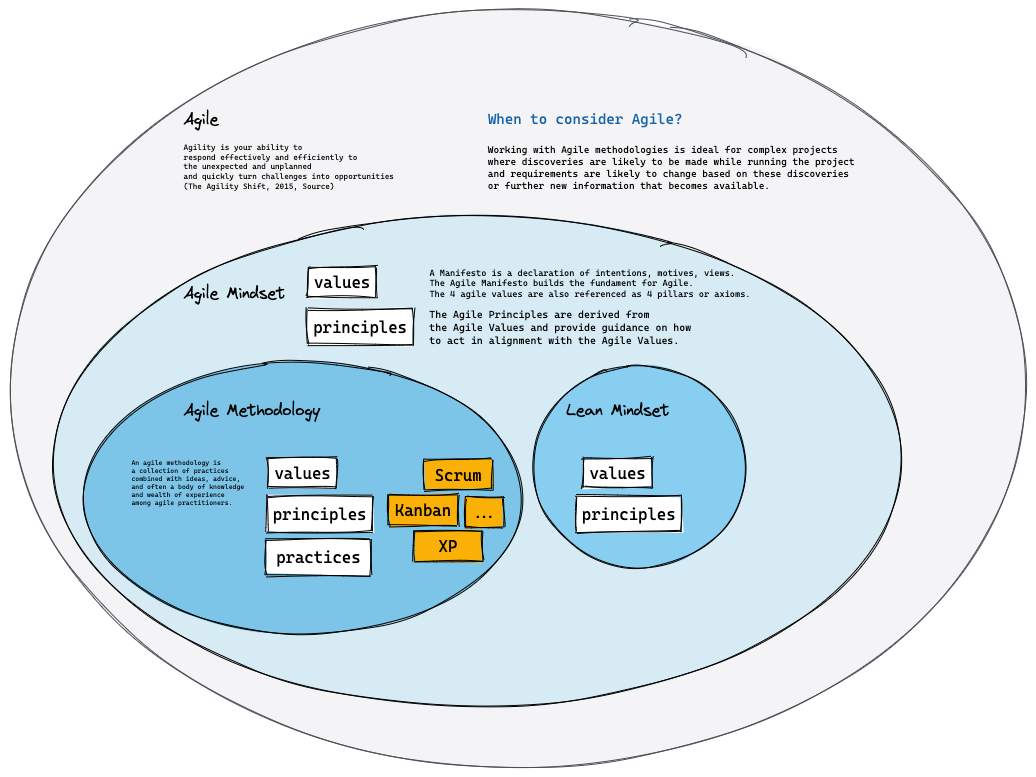

The simplicity of the Agile Landscape, as illustrated above, is deceptive. Its iterative philosophy has given rise to a variety of approaches and models, such as Scrum, Kanban, and XP (Extreme Programming), each offering a slightly different take on how to implement Agile principles effectively. By adopting Agile, organizations can better manage complexity, uncertainty, and the rapid pace of technological transformation.

The Origins of Agile

The Agile Manifesto, written in 2001 by a group of developers and thought leaders, formalized what had been a growing dissatisfaction with the status quo of software development. The signatories sought to elevate collaboration, customer feedback, and flexibility over rigid plans and cumbersome processes. As a reaction to rigid project management models, the creators of the Agile Manifesto introduced four core principles:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools, asserting the importance of human-centric approaches and the power of collaboration.

- Working software over comprehensive documentation, highlighting the need for tangible progress rather than static reports or misaligned documentation.

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation, emphasizing real, continual communication with customers instead of merely enforcing contractual obligations.

- Responding to change over following a plan, recognizing that agility, rather than adherence to a static blueprint, is the key to success in complex, changing environments.

These principles remain foundational to Agile and are seen as a direct challenge to project management approaches that prioritize process, contractual agreements, and extensive long-term planning over real-time responsiveness and continuous improvement.

Variants of Agile

Scrum

Scrum is one of the most popular frameworks for implementing Agile. Developed by Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber, Scrum revolves around defined roles (such as product owner, scrum master, and development team), structured work cycles (sprints), and regular ceremonies (such as sprint reviews, retrospective meetings, and daily stand-ups). Each role and event ensures a clear organizational rhythm and fosters accountability.

The benefits of Scrum include delivering better products faster and more consistently. Each sprint concludes with a potentially shippable product increment, meaning the team provides functional code or another deliverable frequently. However, Scrum isn’t without its critics. Some teams find the rigid structure of roles and meetings constraining, particularly in less software-oriented fields or smaller, cross-functional teams.

Kanban

Kanban, popularized within manufacturing and later applied to Agile teams, emphasizes visualizing work in progress and limiting the number of tasks or items in progress at a time. The Kanban board, usually featuring columns like “To Do,” “In Progress,” and “Done,” enables teams to monitor the flow of work at any given moment. Unlike Scrum, Kanban doesn’t operate using time-boxed sprints, which makes it flexible for teams with operational tasks or continuously changing priorities.

Kanban’s adaptability can be both its strength and its Achilles’ heel. Teams new to Agile sometimes struggle with the lack of pre-defined workflow constraints, which can lead to the overextension of team resources if tasks continuously move into the “In Progress” column.

Principles of Agile

At the heart of Agile are twelve guiding principles closely aligned with the four values of the Agile Manifesto. These principles are essential for understanding how Agile methodologies promote collaboration, rapid production cycles, and adaptability. For example, principle number one prioritizes customer satisfaction through early and continuous delivery of valuable software, ensuring that feedback loops remain short.

Examples of Agile in action often come from companies rapidly adapting to market shifts. For instance, Spotify uses a unique Agile-inspired framework with multidisciplinary “squads” responsible for different features of their product. Each squad conducts its work independently, but also integrates continual user feedback and cross-functionality, mirroring the fluidity of the Agile approach.

In another example, Microsoft adopted Agile practices for its development of the Visual Studio codebase. Moving away from staid, large-scale releases, the company shifted to smaller, iterative builds that allow them to respond more quickly to customer feedback and roll out fixes more frequently.

While Agile encourages rapid output and responds to evolving requirements, some critique its lack of focus on long-term vision or holistic design. Without carefully balancing immediate needs with the future roadmap, teams may find themselves making short-term fixes at the expense of long-term architectural integrity. In highly regulated industries (e.g., finance or healthcare), adhering strictly to Agile may also prove challenging due to the logistical restrictions—such as extensive compliance requirements—imposed on development timelines. Thus, organizations adopting Agile must balance flexibility with the constraints inherent to their industry.

Key Challenges When Implementing Agile

Agile, though widely praised, comes with its own set of challenges. The biggest hurdle many organizations face is the cultural transition. Agile requires a shift in mindset, away from hierarchical, command-and-control structures, and toward empowerment, cross-functional collaboration, and decentralized decision-making. For example, in an organization that has operated top-down for decades, Agile can represent a jarring change because teams are expected to work autonomously, including regular self-management.

Another significant challenge is scaling Agile. While Agile works well for small, fast-moving teams, its application at larger enterprise levels can require adaptations through frameworks like SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework). The complexity of maintaining Agile values and principles while coordinating across multiple, sometimes interdependent, teams can result in inconsistencies in delivery or trades between speed and quality.

Additionally, Agile teams sometimes struggle with stakeholder fatigue, wherein the constant iterative cycles of feedback and review become overwhelming or repetitive. If stakeholders have to be involved in too many reviews or refinements, participation can dwindle, putting the benefits of early feedback loops at risk.

Conclusion

Agile methodologies offer a profound shift in how teams approach product development and project management. By focusing on quick iterations, continuous customer feedback, and adaptability, Agile aligns well with businesses in high-paced industries. However, it is essential for organizations to address the cultural and logistical challenges that come with Agile implementation. Companies should focus on creating an environment that supports collaboration and trust, allowing Agile to truly flourish.

For organizations contemplating an Agile transformation, a focus on education and internal restructuring can help mitigate some of the common pitfalls. By investing in training for both leadership and team members and committing to an iterative process of their own, they can better navigate the growing pains that come with a shift to an Agile mindset. The payoff is clear: responsive, customer-focused teams that deliver valuable, high-quality outputs more efficiently. Forward-looking organizations must act now to adopt or refine their Agile methodologies, ensuring they remain competitive in an increasingly dynamic market.

Original Draft

Introduction to Agile

AgileLandscape.excalidraw.md

Linking

Notes mentioning this note

There are no notes linking to this note.