Forte Labs - Theory of Contraints Blog Series

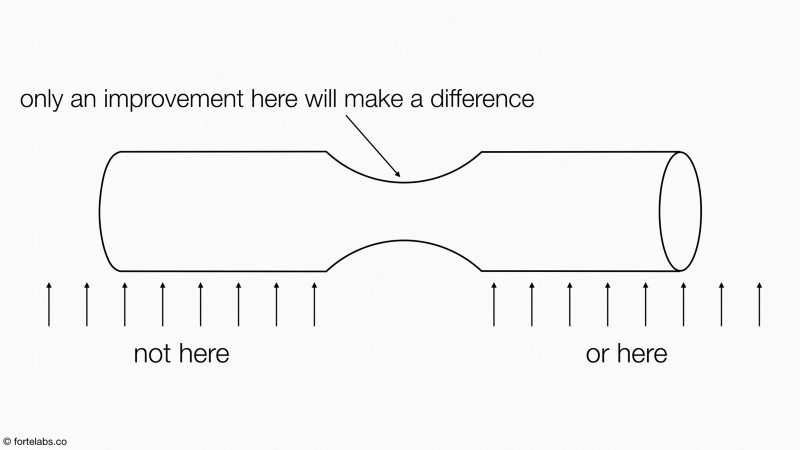

every system has one bottleneck tighter than all the others, in the same way a chain has only one weakest link.

the performance of the system as a whole is limited by the output of the tightest bottleneck or most limiting constraint

the only way to improve the overall performance of the system is to improve the output at the bottleneck (or more broadly, the performance of the constraint)

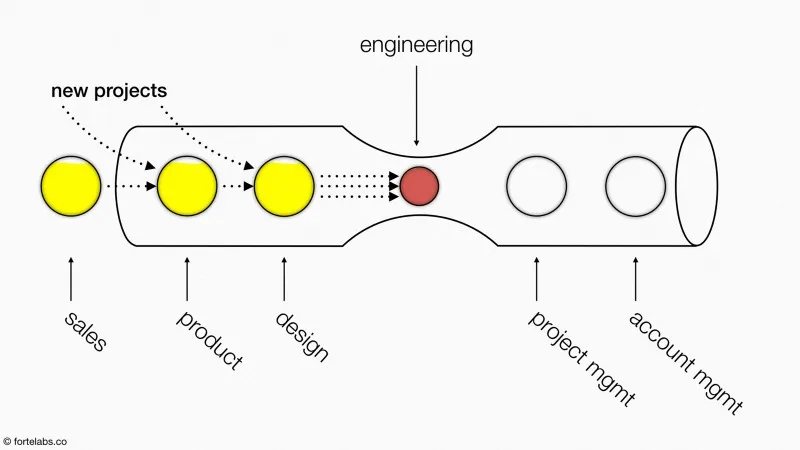

no company should take on more work than their bottleneck can process. The job of management is to determine the capacity of their bottleneck, fill it, and then allow no more projects to begin until one is completed.

for even one part of a system to be fully utilized (the bottleneck), every other part must have excess capacity.

The illusion of local optima

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-102-local-optima/

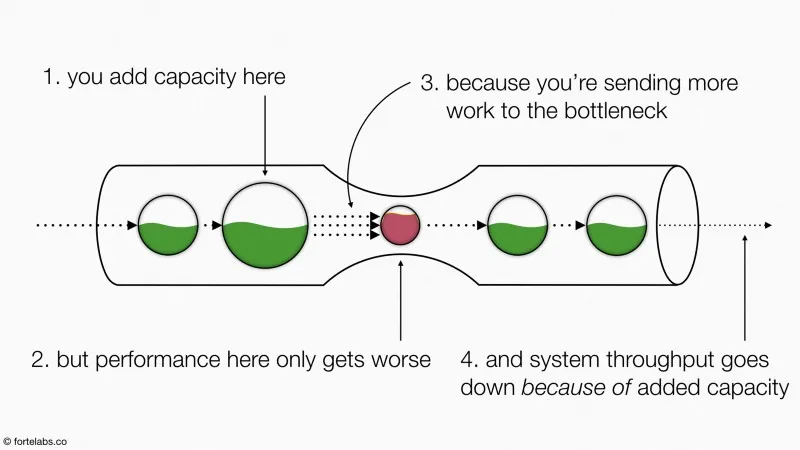

Any improvement not at the constraint is an illusion.

These isolated improvements are known as “local optima” (or in traditional manufacturing contexts, “local efficiencies”). A local optimum is whatever is best for the performance of an individual part, whereas the global optimum is what is best for the performance of the system as a whole.

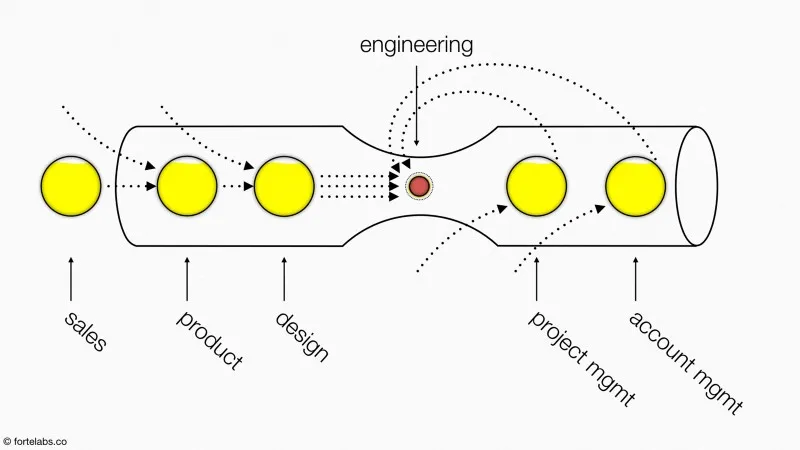

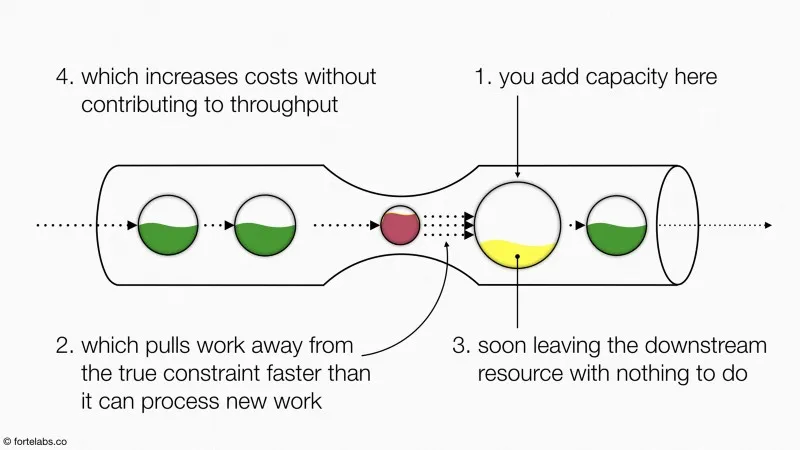

Local optima are not just suboptimal, as in “not as good as they could be.” When combined in an interdependent system, local optima actually make things worse.

But what are Sales, Product, and Design to do? They are operating under the universal rule of the modern workplace: “stay busy.” This unspoken command is a local optimum. They are effectively being told: “optimize for full utilization of capacity at your work center.”

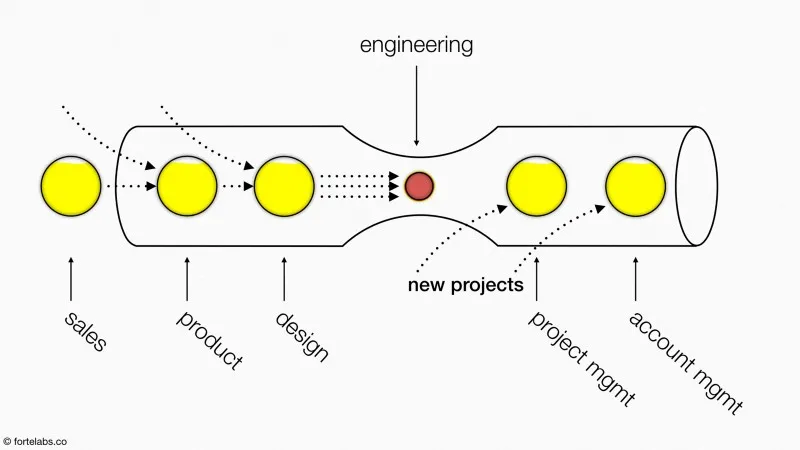

Meanwhile, the same situation is going on in the downstream work centers: they find themselves waiting on work from the bottleneck, and to fill their own capacity, they too start new projects:

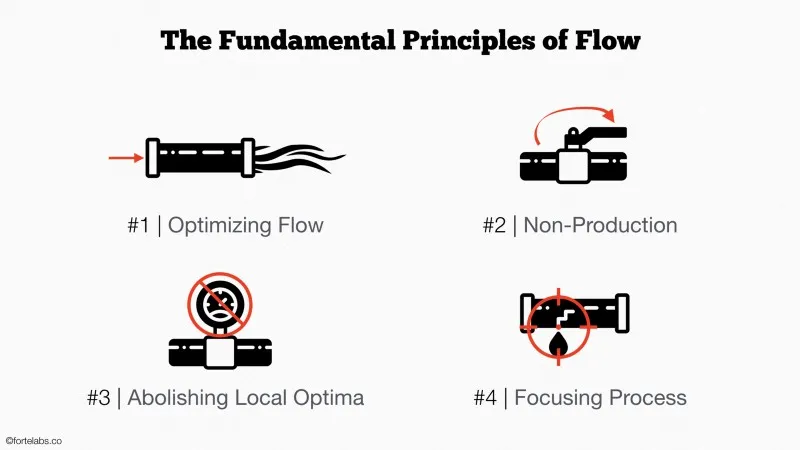

The Four Fundamental principles of Flow

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-103-the-four-fundamental-principles-of-flow/

- Optimizing flow: The primary objective of operations is to improve flow (also known as throughput, defined as revenue minus marginal costs)

- Non-production: The key to improving flow is establishing a practical mechanism to determine when not to produce

- Abolishing local optima: Local efficiencies (better known today as “local optima”) must be abolished

- Focusing process: Improvement must be guided using a focusing process, directed to where it will make the biggest difference at any given time

The power of Kanban was in telling each worker when not to produce.

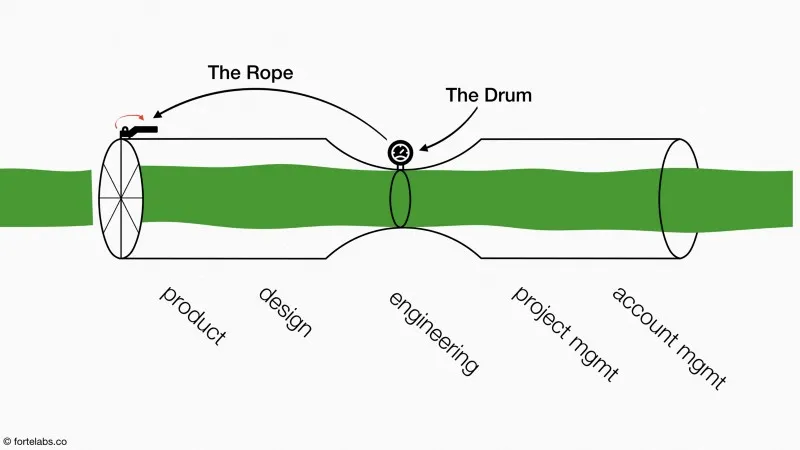

The processing rate of the bottleneck, strategically placed buffers, and the timing of “release of materials.” These correspond to the three main parts of the manufacturing production system Goldratt designed: Drum-Buffer-Rope.

In all these creative fields, work moves not through the sequential, linear flow of an assembly line, but the even more rigid, even more linear flow of time.

The Five focussing steps

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-106-the-five-focusing-steps/

IDENTIFY THE CONSTRAINT

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-107-identifying-the-constraint/ The reassuring truth is that you don’t have to identify it perfectly from the very beginning. This is a self-correcting process, not a waterfall where small errors in the beginning become huge mistakes by the end. The advantage of working with a dynamic, interconnected system is that it responds very quickly to changes. The behavior of the system tells you whether you chose correctly.

Instead of collecting vast amounts of data on every aspect of the business, we make our best guess as to where the constraint lies, and let reality be our guide. Instead of spending vast amounts of time making a detailed plan covering every contingency, we acknowledge that we don’t have answers, only hypotheses.

Steps

First, you have to make work-in-progress visible. Because information work doesn’t usually have a physical manifestation, much of modern productivity starts with making it tangible: kanban boards, gantt charts, burndown charts, to do lists, calendars, and timesheets create visual displays where workloads and progress can be evaluated more easily.

Second, look for the most scarce resources. At an individual level, look for those tasks on your calendar or to do list that get repeatedly pushed back and rolled over. These tend to be tasks that require certain types of resources — skills, states of mind, tools, blocks of time, or the presence of others — that are in short supply. If your personal constraint is dedicated focus time, for example, then tasks that require such time will accumulate and get delayed, an experience familiar to many.

The constraint in the flow of work will be the step with the longest average cycle time.

Third, ask people. Using the visual measures and data collection from the previous two steps as a cross-check, simply ask your people: what is the resource you are most often waiting on? (tip: it helps to use the term “most scarce resource” instead of “bottleneck” to avoid bruised feelings)

At what point in product development are there most likely to be “quality cycles” — back-and-forths, quality checks, or rework. Often blamed on “uncertainty” or treated as “iterations,” such cycles represent work moving backward through the system, and are a ripe target for standardization and process improvement.

Fourth, look for constraining policies and rules. It is tempting in the initial surge of constraint-hunting excitement to tackle what looks like the “biggest and scariest” problem. It seems logical that the “squeakiest wheel” that everyone complains about must offer the biggest gains.

A freakishly dysfunctional machine would quickly collapse under the laws of physics, while a freakishly dysfunctional company policy might warp the behavior of employees for years before anyone realizes what is happening. It is harder to point out the damaging effects of such policies, because they live in the minds of people.

It is not difficult at this point to convince everyone that their job is to do whatever it takes to maximize the constraint’s productivity, instead of working as many hours as possible.

OPTIMIZE THE CONSTRAINT

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-108-optimizing-the-constraint/

Before adding capacity, we need to use the capacity we already have. “Optimize” in this sense means “doing everything possible to use the constraint to its fullest capacity.”

Buffers: how can you pre-prepare and pre-package units of work, to make sure the constraint never runs out of work and goes idle?

Quality checks: how can you check the quality of work before it goes through the constraint, to be sure that it doesn’t waste time on unnecessary tasks?

Continuous operation: how can you make sure the constraint is running as much of the available time as possible?

It could also take the form of catered lunches, company shuttles, or no-meeting days. Anything that saves the employees’ time potentially increases the number of hours they could be working.

Preventative maintenance: what actions could you take in advance to reduce the chance of a breakdown that might interrupt the constraint?

But in knowledge work, it also means preventing emotional and health breakdowns — offering benefits and incentives that encourage employees to exercise, eat well, get enough sleep, take care of their health, and even engage in volunteering and other activities that connect them with a higher purpose.

Offloading: which tasks that the constraint is currently performing could be performed by other resources?

5S: how could the constraint’s work environment be organized to promote efficiency, effectiveness, and order? For knowledge work, this could include everything from clean, visually pleasing offices with minimal clutter; to equipping employees with late-model computers and user-friendly software; to standardizing how digital files are named, stored, and updated.

Andon: how can we make it easier and faster for constrained resources to surface and solve problems? Andon is really about creating a culture that treats problems as “jewels to be treasured,” not mistakes to be hidden or blamed on someone.

SUBORDINATE THE NON-CONSTRAINTS

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-109-the-psychology-of-subordination/ The job of all non-constraints is to subordinate their decisions to the constraint’s needs. They should optimize for constraint (and thus system) performance, not their own individual performance

And they need to do it fast, before an interruption strikes again. They can only do this if they have excess (or sprint) capacity. This is why for even one part of a system to be fully utilized (the bottleneck), every other part must have excess capacity.

Besides being the least appreciated, the least intuitive, and the most political, subordination is also the most difficult step. It is directly opposed to what Goldratt described as the #1 rule of the workplace: stay busy.

Another example of subordination is expediting. It is a decision to subordinate all the carefully planned work of the organization or team — current projects, release dates, prioritized requirements, batch setups, and agreed schedules — to a crisis. The sensation is that we are accelerating the emergency request through the usual steps. In reality, we are slowing down the entire system to free up the capacity needed to do so.

Employees themselves make sure they stay busy, making it hard for managers to even judge where the real constraint lies.

When a non-constraint overproduces and piles up a bunch of knowledge work inventory in front of a constraint, it is like a grocery store supplier piling up a mountain of ice cream tubs outside the freezer because they didn’t bother to find out how much capacity it had. When this ice cream melts (the ideas and requirements become outdated), the entire cost of producing them (researching, analyzing, updating, reviewing, summarizing, etc.) has to be written off as operating expense, instead of counted as investment.

ELEVATE THE CONSTRAINT

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-110-elevating-the-constraint/ Only once we’ve completed the previous steps does it make sense to add more constraint capacity, and thereby increase system performance. Because adding capacity is tremendously expensive in terms of time and money, we do it as a last resort, not a first resort.

TRACKING PERFORMANCE DATA

Your goal is to identify and then fix the top sources of lost time using cross-functional teams.

Reviews

The Lean technique of Poka-Yoke (definitely the best Japanese Lean term, by the way) advises building defect detection and prevention into the equipment itself. This would be the modern equivalent of advising people to choose stronger passwords right when they’re creating an account.

SETUP REDUCTION

Automating deployment, integration, and testing for software programmers, or using templates or style guides for designers.

UPDATES/UPGRADES

This could include proactively scheduling updates and upgrades to avoid unnecessary downtime

INCREASE CAPACITY

Note that the economics of doing so are completely different than for the typical hire: it makes sense to hire even extremely expensive or extremely unproductive resources, because every unit of capacity at the constraint is worth the throughput of the whole organization. But because adding any capacity is extremely expensive in terms of time and money, we do it as a last resort, instead of a first resort.

Resolve POLICY CONSTRAINTS

PARADIGM CONSTRAINTS

They are the blindspots and the assumptions, the worldviews and the filters that enable, but also limit, our view of reality.

RETURN TO STEP 1

Balance Flow, Not Capacity - Drum Buffer Rope

https://fortelabs.co/blog/theory-of-constraints-104-balance-flow-not-capacity/

How do we operate the system to achieve maximum throughput?

DBR is designed to enforce this: the processing rate of the bottleneck is the “Drum” that determines the pace at which the entire system should work (like a drummer in a marching band helping the whole group step in sync). The “Rope” is the signal that “pulls” a new item of work into the pipe only when an item is processed by the bottleneck (the same role played by Ford’s belts and Ohno’s kanban cards earlier).

Any part of a system that needs protection from uncertainty, variation, or disturbances in the environment, while still interacting with that environment, requires some sort of buffer.

Every single minute of lost time at the bottleneck must be counted as a lost minute for the entire system.

Therefore, we must ensure that the bottleneck never goes idle for any reason. The only way to do that is to stockpile work-in-process in a queue in front of it, so it will always have something to work on even if the flow from upstream gets temporarily interrupted.

Much of what constrains the productivity of software engineers (and by extension, other knowledge workers) is not related to the details of how they perform their work, but to the management, planning, scheduling, and queueing of work.

Critical Chain project management

Resources

[[The Goal]]